4 min read

No Receipt? No Problem. How Fraudsters use Merchandise Returns to Make Millions

![]() Jessica Mitchell

:

November 18, 2019

Jessica Mitchell

:

November 18, 2019

As holiday shopping increases, so do the opportunities for Organized Retail Crime.

“Theft from retail establishments has long been a problem,” – according to Rep. Robert C. Scott, (VA), Chairman of the House Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security back in November 2009 – “but the problem gradually grew beyond simple, isolated incidences of shoplifting and burglary into something more complex.” It wasn’t until the 1980’s, he added, “that organized retail crime was recognized as a phenomenon, but the problem has continued to grow in volume, sophistication, and scope.”[1] Scott also noted that Organized Retail Crime doesn’t just hurt the stores from which the criminals steal the merchandise, but also the consumer population in general who must bear the cost of heightened in-store security, and the state and local governments who lose tax revenue.

Ten years later, and Organized Retail Crime continues to grow in volume, sophistication, and scope.

Though the definition varies by jurisdiction, Organized Retail Crime generally involves the association of two or more persons engaged in illegally obtaining retail merchandise in substantial quantities through both theft and fraud as part of an unlawful commercial enterprise.[2] According to the National Retail Federation’s (NRF’s) 2018 Organized Retail Crime Survey[3], retailers estimate that almost 10 percent of all returns are likely to be fraudulent. These fraudulent returns are committed by individuals, small groups, and complex criminal rings. With the NRF projecting retail sales in November and December of 2019 to reach $730.7 billion[4] that means retail stores and financial institutions may suffer losses from fraudulent returns in the billions of dollars.

Fraudulent Returns are a Type of Organized Retail Crime; known as Merchandise Return Fraud, these fraudulent returns are made without receipts and are more likely to occur in the country’s largest cities, including New York City, Los Angeles, Miami, Chicago and Houston.

The criminals who perpetrate these frauds are developing more complex schemes in an effort to by-pass heightened in-store security, better fraud-detection computer software, and increased awareness of common red flags (noted below). These schemes often employ multiple individuals and many utilize legitimate websites to launder their “dirty” merchandise credits.

Today, fraudsters typically employ two variations of the Merchandise Return Fraud.

The first requires fraudsters to visit one location of a brick-and-mortar store and steal merchandise, then visit a second location and return the goods for merchandise credit. The fraudsters then sell the merchandise credits directly to individuals and businesses, or, as is becoming more common, sell the merchandise credits to third party gift card retailer websites.

The second requires fraudsters to open credit card accounts under fake or assumed identities. The fraudsters use the credit cards to purchase merchandise, return the items without a receipt for merchandise credit, and then sell the merchandise credits to individuals, businesses, or third party gift card retailer websites.

Retailers and Financial Institutions, in response, have been employing fraud-detection software.

These programs gather point-of-sale (POS) transactions, spikes in account activity and merchandise returns, and other data used to detect fraudulent activity. Audio recordings, photos, and video recordings are also gathered and analyzed. Companies even offer fraud detection software that can assist retailers and Financial Institutions with modeling that predicts the number of product returns per shift.

But, just as the methods of detecting and preventing these frauds have become more sophisticated, so too have the schemes.

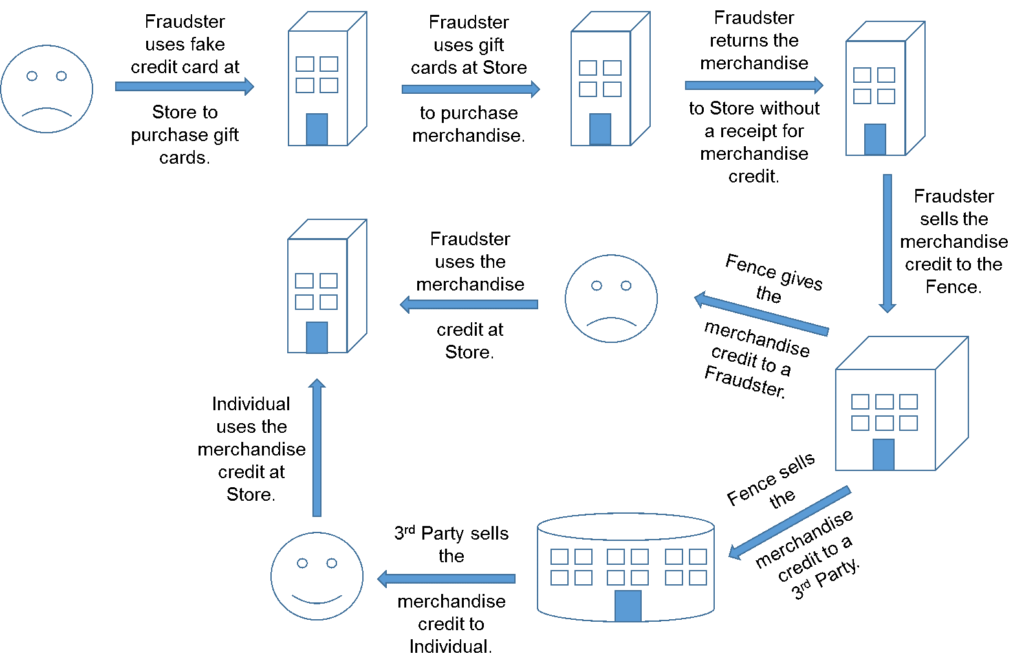

In July 2019, a grand jury indicted 13 people for running a scam that brought in almost $1 million per month for two years. According to the 192-count indictment filed in the Queens Supreme Court in Queens, New York, two brothers from New York oversaw the fraud ring, which utilized a fake cover business, also known as a “fence.” According to the Queen’s District Attorney’s Office, the fence employed “a fence manager, swipers, shoppers, fence employees, money launders and more.”[5] The swipers would obtain credit card numbers from the dark web, create new credit cards, and use the fake cards to buy retail gift cards. In order to give the gift cards a “clean” record and make it more difficult for retailers and law enforcement to link the gift cards to stolen credit card numbers, the swipers would purchase merchandise with the gift cards, return the items without a receipt for merchandise credit, and “sell” the merchandise credits to the fence. According to the indictment, the brothers’ wives would then use the “clean” gift cards to furnish a lavish lifestyle. The ring also sold gift cards to the third part sites mentioned above and laundered the money received through the fence. A simplified illustration of this complex ring is provided below.

In September 2019, a Flint, Michigan resident was arrested at a retail store in Madison, Wisconsin for his role in a unique variation of the merchandise return fraud. The Michigan resident visited a retailer, selected items to purchase, and took the items to the counter to pay. Using what he described as a “Global Cash Card,” the criminal told the retail store associate that in order for the transaction to process on his card, the associate would need to press “Cash” on the point-of-sale system and input the amount of the transaction. The fraudster then pretended to swipe his card and the associate handed him a receipt for the items. In reality, the card was bogus and the associate processed the transaction as if the suspect paid in cash. The suspect was apprehended at a second retail store location, where he was in the process of returning the stolen goods for merchandise credit.

There are some common red flags for which retailers and Financial Institutions should be on the lookout:

- Excessive returns without a receipt;

- Excessive returns at multiple retail store locations;

- Excessive credit usage within a short time of account opening;

- A customer’s request that the transaction be entered into the point-of-sale system in a specific way that is contrary to typical methods (e.g., asking the associate to press “Cash” when using a credit card); and

- Business accounts with excessive payments to or credits from third party gift card retailer websites.

Merchandise Return Fraud scams ruin the credit scores of thousands of individuals while costing retailers and financial institutions millions of dollars each year. Contact AML RightSource to discuss how we can assist your institution with detecting and preventing Merchandise Return Fraud and other versions of Organized Retail Crime.

[1] https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-111hhrg53231/html/CHRG-111hhrg53231.htm

[2] https://losspreventionmedia.com/lp-101-organized-retail-crime/

[3] https://nrf.com/research/2018-organized-retail-crime-survey

[4] https://nrf.com/media-center/press-releases/nrf-forecasts-holiday-sales-will-grow-between-38-and-42-percent

[5] http://www.queensda.org/newpressreleases/2019/JULY%202019/nathoo_brothers_%20and%20_11_giftcardscam_07_10_2019_ind.pdf